Dr Maryam Farahani – July 2022

Health and beauty classifications are controversial topics in humanities and sciences, but they are also inevitable concepts upon which people ponder in the path of self-discovery. In their edited volume, Narrative Art and the Politics of Health (Anthem, 2021), Neil Brooks and Sarah Blanchette aptly argued, “as scientific advances provide insight into a wide range of well-being issues and help extend life, it is vital that we come to question the very categories of healthy and unhealthy.” I want to address this topic considering one aspect of women’s lives and that is the athletic domain. For women in the world of professional athleticism, managing health-beauty classifications and mitigating the risks involved may be a little different compared with non-athletic women. Professional athletes try to push the boundaries of human performance, thriving through physical and mental processes, but often showcasing illness (rather than health or beauty) as sporting narratives. Once on the international podium, such narratives of medal-winning illnesses may illustrate the political dynamics of national aspirations in each country’s championship ranking. This way, illness not only defeats the objectives of athleticism but also undermines the realities of challenges faced by often very young women and men.

Drawing on the conception of health and illness, Brooks and Blanchette (2021) confer,

Notable works such as Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor (1978) and Emily Martin’s Flexible Bodies(1994) exemplify how illnesses–such as cancer or AIDS–are metaphorically positioned in medical discourse in terms of militaristic interventions or the defense of a nation-state against intruders. Consequently, the health humanities elucidate the ways in which health care is already, and has always been, deeply enmeshed within narrative, in order to problematize the privileging of allegedly objective scientific narratives of illness over others (Narrative Art and the Politics of Health, 8).

This reminds me of the realities of watching medicated sports and the scientific impact that Olympic teams’ healthcare professionals bring to scientize human performance in today’s global competitions. Let us think, for example, of top women figure skaters. Despite her victory, Russia’s Anna Shcherbakova, who won the singles gold medal for women’s figure skating in Beijing 2022 Winter Olympics, expressed a feeling of numbness. Her teammate Kamila Valieva broke down in tears after falling while her presence in this year’s Olympics was clouded by a doping scandal. Not long ago, Julia Lipnitskaya, another star in the Russian squad, battled anorexia which in clinical terms is viewed as an illness rather than healthy athleticism. These young women have given the world the gift of extraordinary and superbly artistic and athletic exhibitions. Watching them perform is pure joy but noticing how they suffer is a melancholy contemplation. In Aug 2017, Lipnitskaya retired from competitive skating at the age of only 19. It is understood that “eating disorders have been described as “skating’s dirty little secret.” But, in recent years, the unhealthy bar has been raised even further to ensure national success for top competitors.

Lipnitskaya at the 2014 Winter Olympics

One example is aspiring to perform near-to-impossible technical elements. The normal quadruple (quad jump) performed by Valieva is one element that has only since 2018 become fashionable among women figure skaters. It is, however, an essential part of male figure skaters’ routine in national and international competitions, to the point that not performing a quad would handicap men in terms of medals and ranking. The main requirement for this element is 4 full revolutions above the ground and landing on one foot; a move which is transforming women’s figure skating. It is particularly a difficult jump for women’s body types, unless a certain level of physical transformation is achieved to align female features to the masculine symmetrical body shape. The quad variation with four-and-a-half revolutions is called quad axel, performed by taking off while facing forward and landing on the ice backwardly; yet to be achieved by any woman skater. In Olympics 2022, a male figure skater, Yuzuru Hanyu demonstrated this rather unusual and difficult skill, expressing how he has given it all he could. And, as for quintuple jumps, they are a dream for the future both for women and men figure skaters, the biomechanics of which are yet to be developed and learned by the human brain and body.

However, for both men and women, maintaining balance is central to success in figure skating and it relies on keeping the center of body mass directly over the contacting point on ice. As Evelyn Lamb explains:

For a highly symmetric object like a circle or sphere, that is in the dead center. For the lumpier, bumpier shape of the human body, the center of mass varies from person to person but tends to be a bit below the navel. Through glides, spins, takeoffs and landings, a figure skater has to keep their center of mass aligned with a foot on the ice, or risk taking a tumble.

This is an example where starving the body and reducing overall weight (to create a more symmetrical shape) becomes the unhealthy goal. Athletes’ heights-versus-weights, on the other hand, is a controversial matter; the shorter and more agile differs the taller and more powerful. Both groups may achieve excellent spins in the air so long as they can comply with the rules of physics, efficiently pulling their length/weight in the air; it is a lot to do with stamina, agility, decision-making in seconds, and high level of confidence and risk-taking; a combination of mental and physical skills. However, as seen in this year’s Olympics, scientific advances are applied to change body shapes and healthy diets for the sake of medal figures. Can we say that figure skating is moving toward a healthier and more beautiful direction for women? I am not quite sure.

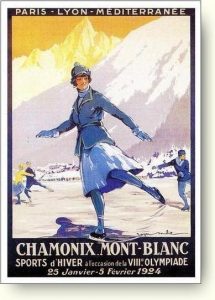

Organized by the French Olympic Committee, the first Olympic Winter Games was hosted in Chamonix, France (25 January to 5 February, 1924), showcasing 10 days of excellent athleticism. In those days, the world of women’s competitive figure skating was not filled with what I see as medicated performance to the extent that today we are witnessing as a result of extreme diets and puberty-blockers to stop breasts growing and halting menstruation. Anastasia Kuprinya expressed concerns in 2020, confirming that “there are always side-effects, such as problems with your nervous system and your heart that no one really talks about.” Laura Clawson argues that women are suffering irreparable harm: facing regular verbal and physical abuse, daily weigh-ins, competing while injured, tearfully breaking down at the point of falling, suffering early menopause, fainting with pain after their routines, and ultimately retiring early. In reality, women are not achieving health or beauty with such strict regimes of training, medicating, and dieting, but they are suffering during their most youthful years of life.

A 1924 Winter Olympic Poster

Beyond the athletic technicality, artistry, and elegance, there are serious risks involved in figure skating. 30 years ago, Surya Bonaly, was the first female skater who started women’s quads in addition to performing a controversial backflip in her free program in the 1998 Nagano Olympics. Backflips are still considered too dangerous; in fact, an illegal move. However, Bonaly’s body was not Lupron-induced, emaciated, or symmetrically transformed by medication. Yet, her performances were stunning. Moreover, some suggest that Bonaly broke barriers, not just as a female athlete, but as a black figure skater and, yet unsurprisingly, she faced negative judgement. Nicolette Didone argues that figure skating, predominantly white, has governing bodies who enact rules subjectively, based on their implicit judgments about what are the appropriate artistic ways for skaters to present. Didone contends that

Bonaly did not fit into the traditional image of a thin, often white ice princess stereotype that figure skating continues to uphold. Sports media legitimizes social inequality by highlighting the physical and personal attributes of Black athletes while shying away from the social structure of the system that continues to disproportionately affect people of color more broadly.

Bonaly performing at a gala in 2007

Aspiring to team excellence calls for group-growth approaches to winning Olympic medals. I remain, however, doubtful of the underlying motives that drive teams, coaches, doctors, and young women to risk harming bodies and minds in order to fulfill medal figures and ranking. Social media, nevertheless, offers one glimmer of hope by presenting athletes’ narratives in such a way that can be accessed first-hand and evaluated for research which is much needed in this area. As Aaron Martin et al. conclude in Narrative Art (2021), while “pragmatically informed stories emphasize experience-based accounts, a genuine outcome of substantively alleviating suffering becomes an effective means for displaying the concrete repercussions of health-related narratives”. Given that the Olympics expose success with so-called health narratives, it is not hard to imagine why athletes such as Shcherbakova feel numb. How else could anyone feel at the end of an extraordinary medal-winning routine, demonstrating ideals of excellence physical performance but suffering ill health? Perhaps it is fitting to remind ourselves of Kimberly Brown Pellum’s words in 2019 that “the beauty ideal, together with its unattainability, as a political apparatus designed to tighten around the necks of women as they advance in society” is still a subject for further scrutiny in research, in medicine, in ethics, and most importantly by women.

Maryam Farahani is a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool and co-editor of Psycho-Literary Perspectives in Multimodal Contexts. She is an accredited leadership and education management practitioner and social psychologist, reading narratology, history of medicine, and philosophy of mind and is authorized in team and personality assessment. Her forthcoming monograph (in 2 vols) entitled British Women’s Poetry & the Psychology of Aesthetics explores nineteenth-century women’s verse narratives in the cognitive field.