The guest author for this post is Maryam Farahani, She is a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool and co-editor of Psycho-Literary Perspectives in Multimodal Contexts.

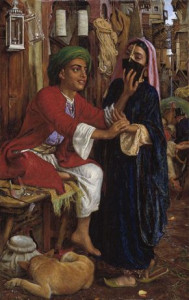

During the long nineteenth century, Western Orientalists designed intimate portraits of the East, informed by new aesthetic principles. William Holman Hunt (1827-1910), for instance, painted a striking icon of Oriental romantic interaction, sketching the social distancing norm in A Street Scene in Cairo (1854-61). The Egyptian woman in niqab (the veil) symbolises the erotic-exotic binary in female form. Although the niqab has been shunned in the past decade and lost its aesthetic appeal for our Western imagination, it remains to be a protective attire in social distancing. The historical function of the niqab for women communicates aesthetics of virtue, which Thomas Reid (1710-1796) specified as an aspect of beauty in his theories of taste and perception.

When authors of a 2013 MERS study suggested gender difference and infection rate, reiterating that Saudi women wearing the niqab might have better protection, the proposition was immediately challenged by Western thinkers. Today, Muslim women are not receiving the usual hostility while the public are advised to wear face-masks as a means of “protection” and “prevention of transmission” during the Coronavirus pandemic. I wonder whether excessive cautionary strategies can become a double-edged sword in the long run. Could we be reminiscing our historical fear of the unknown and over-indulgence in debating gender differences? Could extreme ideas of social distancing entwined with economic distancing increase global paranoia? I argue that behavioural paradigms, the battle of the sexes, and biases engrained in societies are among credible historical reasons to concern us regarding generational patterns of paranoia.

Review, for instance, western colonial-era intellectuals demonstrating women as objects of eroticism: ripe and plump concubines, sensual women in Turkish baths, reclining healthy slaves in Ottoman Harems, and stylishly-dressed girls in lavish Persian anderoonies. These images inspired fear and attraction, encouraging exploration and exploitation beyond the veil, insofar as some artists even endeavored to cherish such fantasy worlds. Epistolary narratives testify to certain madness in Western obsession with erotic-exotic binaries or as Holman Hunt put it, “Oriental Mania”.

The European quest for feminine health and beauty transported Western men across the continent on to the Middle East. But there was another reason, beyond trade, art, sensual women, and geopolitics, that directed them eastwards.

Escaping diseases and epidemics prompted health tourism and, for some, even permanent settlement in the East. Theories of disease transmission, such as in the case of syphilis, were known by Columbian and pre-Columbian hypotheses, yet never recorded as an Oriental infection. In my reading, so much as I hoped to understand whether Westerners were concerned at all about transmitting diseases to the local communities overseas, I have not so far reached cumulative evidence.

It is documented that the British upper classes, who could afford travelling to health-resorts abroad, made health tourism a fashionable practice. One of my favourite writers, Lady Lucie Duff Gordon (1821-1869), left England, for South Africa and Upper Egypt in the 1860s. Unlike her male counterparts, she was not journeying for fictive adventures or political power. Lucie was fond of translation but did not dare entering masculine literary circles by penning poetry or fiction. Perhaps she was aware that other literary women such as Felicia Hemans (1793-1835) struggled.

Lucie travelled to Egypt, learned Arabic, and settled for the rest of her life, in the hope of real healing. She was afflicted with tuberculosis in England and grief-stricken after losing her 6-month-old son. Her desire to travel was fortified by her fondness for observational learning and the new British tourism in Egypt; she reflected on her friends’ experiences, such as William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863) and Bartholomew Elliot Warburton (1810–1852). Upon returning from the East, they discussed positive and soulful transformations as a matter of social distancing from Western intellectual circles. Warburton even published his first book, the Crescent and the Cross (1844), inspired by his Middle Eastern journeys.

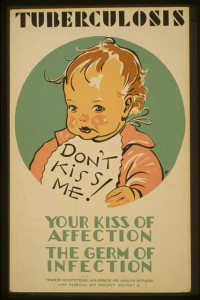

By the mid-1850s, tuberculosis had become a deadly epidemic, taking lives all over Europe, including some of my favourite English poets, John Keats (1795-1821), Emily Brontë (1818-1848), and Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861). In the 1800s, up to 25% of deaths in Europe were attributed to TB. In 1830-1833 and 1836-1837 respectively, influenza epidemics broke out in England and, from 1826 to 1837, London saw the worst of a second cholera wave. Social and economic distancing strategies did not save British upper classes from disease and death. The first posters about prevention of TB transmission appeared in the US almost a century later, but earlier artistic efforts culminated in typical eroticized portraiture of female organs. La Miseria by Cristóbal Rojas (1857-1890) was painted in 1886 when the artist himself was battling TB. The disease is eroticized in a non-Oriental, pensive anesthetisation of naked female anatomy.

Figure 5. Tuberculosis Don’t kiss me! Your kiss of affection, the germ of infection (1936-1941), NY: Library of Congress.

Such emaciated images of diseased women were a far cry from the Western desired models of exotic beauty. I, therefore, contend that the conception of “consumptive chic”, proposed by some of our contemporary Western feminist scholars, is not accurately identical with health and aesthetic standards seen through the nineteenth-century masculine gaze. For these men, curvaceousness was an agreeable norm of health throughout the seventeenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. This was, of course, not a Rubenesque type of female nude, but neither was it corroborating the pale and thin female consumptive model which appeared in the latter part of the nineteenth century. That is why I do not endorse the “aestheticization of tuberculosis” as an accurate judgement of health in literary and visual arts of the period. Moreover, for many women writers of the time, such as Lucie and her historian daughter, Janet Ross (1842-1927), livelihood and physical strength, as well as well-built constitutions identified with aesthetics of health rather than pensive moods and consumptive bodies.

“Change in climate” was Lucie’s prescription by London specialists such as Dr Quail and Dr Izod. In Egypt, her Luxor letters were enthralled by realistic Oriental images of private and public spheres. Despite her humorous tone, Lucie had formed her own biases and tenacities, frequent in colonial travel writing of the time. In Luxor, she became not only a convalescing patient, but also a Hakima (female doctor). During one Ramadan, an epidemic broke out with symptoms of gastric fever. She refused to heed warning and aided the poor with her medicine box with supplies and a “lavement machine” to give effective enemas. Her efforts proved nothing short of a miracle and she saved anyone she could treat early on. Although it seemed that in her Oriental journey, escaping Western influenza and TB epidemics, Lucie had faced another epidemic in the East, she made the most of life. Providing medical help to the community gave her a new purpose in the spring of 1864 which she followed until her death. According to Katherine Frank (1994), Lucie’s biographer, it was in Egypt that she found new peace, new friendships, new social distancing benefits from spurious London aspirations, and new wholeness. She was called Noor ala Noor by Egyptians, meaning a light brighter than her original name, Lucie. Through epidemics, grief, illness, pain, loss, and sorrow, Lucie found new light. Perhaps we too may find a transformative healing, if not a temporary escapade from our Western freedoms to our private lockdowns. As Katherine Frank put it:

“But human beings, like all things, shed chrysalises, moult, slough off old skins, metamorphose, discard, and assume names, rise from heaps of old ashes…

Maryam Farahani is a Research Associate at the University of Liverpool and co-editor of Psycho-Literary Perspectives in Multimodal Contexts. She is an accredited education management practitioner, mentor, and coach, reading narratology, history of medicine, and philosophy of mind. Her forthcoming monograph (in 2 vols) entitled British Women’s Poetry & the Psychology of Aesthetics explores nineteenth-century women’s verse narratives in the cognitive field.